At the helm of the Gabinete de Arquitectura in Asunción, Paraguay, is architect Solano Benitez. The geography of this relatively small country at the heart of South America explains some of the main features of the Gabinete’s work. Paraguay can be seen as an iconic image of the continent. It is a nation with a weak economy (a ‘developing country’, euphemistically speaking) and a hybrid culture marked by Spanish and indigenous Guaraní influences. Paraguay has a hot, wet climate, vast forests and mighty rivers. Writing about its physical and political make-up, author Augusto Roa Bastos called his country ‘an island surrounded by land’.

These characteristics, some of which pose constraints to design, have enhanced the work of the Gabinete de Arquitectura. Tight budgets and regional building practices have led Benitez to prioritize methods of construction over other factors. Taking brick as a starting point – a cheap material produced locally – he attempts to make imaginative use of an ordinary product while expanding its possibilities. Benitez says that Paraguay is going through a ‘crisis due to a failure of imagination’. Lacking an instant solution to the problem, he engages in an ongoing process of invention and trial.

Because of the architect’s approach, the company he runs is a multifaceted operation. Both studio and workshop, the Gabinete is a hive of design, construction, education and research. The space that houses the studio – a building site in itself – is in constant flux. The development of construction methods is essential for a design process that moves from studio to building site and back again, combining the professional knowledge, craftsmanship and intuition of everyone involved. What’s more, Benitez surrounds himself with young architects who contribute enthusiasm and inventiveness to the mix, while often claiming to have forgotten much of what they learned at school.

Although building techniques form the core of his work, Benitez’s projects are not primarily technological. In an environment of extreme temperatures, he sees the construction process as a means of generating space surrounded by a shell. The use of brick naturalizes, so to speak, the physical presence of his buildings. By designing elements that fragment the exterior and fold into the interior, Benitez creates intermediate spaces that address problems relating to climate and programme. This and similar spatial solutions can be found throughout the work of the Gabinete de Arquitectura: in the façade and courtyard of Unilever Headquarters, for instance; in the concrete beams that generate space in the tomb he built for his father; and in the brick vaults of the Teletón Rehabilitation Center. The best example, though, is Esmeraldina House, whose three-storey brick wall – made from precast panels that are only 5 cm thick – achieves its stability from its folded geometry.

Another of Benitez’s interests is poetry, which he calls ‘a technique to satisfy the mental needs of human beings’. Poetry helps him to build his projects and to explain the work as well. Reflecting the use of synthesis, poetry condenses ideas and images into words or forms that it delivers in a forceful way. In physical terms, we can say that the Gabinete de Arquitectura produces precisely calculated forms made of a single material, but the force of these structures – a force arising from space, light and matter – conveys a deep message in a simple way, on an emotional rather than a rational level. The thought that goes into such forms may not be simple, but the result certainly is, thanks to careful refinement. As far as explanations are concerned, Benitez often refers to literature and philosophy in his speeches at conferences and seminars, expanding the scope of his projects into the realm of the imagination.

The main feature of the work is its consistency. By allowing for a process of invention and trial, the Gabinete leaves room for error in its quest for the best possible solution. Interestingly, this way of working leads to a very coherent body of work that’s more about the process than the final result.

French architect Anne Lacaton, whose work can be compared to that of Benitez with respect to the use of resources, has said that ‘luxury is not founded on money, but on transcending expectation’. To use restrictions as an advantage, without wasting resources in the process; to opt for a noble but inexpensive material, opening up its possibilities to unexpected uses; to generate space for the soul and comfort for the body, and to do it with beauty – such is the essence of luxury. In this sense, Benitez makes luxurious buildings, while simultaneously rousing interest in architecture as a discipline and drawing attention to the contemporary architecture of Paraguay.

Las Anitas House, Santani, Paraguay 2008

In the countryside, 200 km from Asunción, is the elongated Las Anitas House, a single volume that faces a landing strip. Interior spaces offer occupants various levels of privacy, from collective to individual. Two mezzanines have been inserted between the inner and outer walls of the house. The pocket of air captured between these walls provides insulation. On the east side is a folded, self-supporting brick wall that is 5 cm thick, 36 m long and 6 m high. The wall not only generates circulation that leads to the bedrooms, but also emerges as a second layer of the façade, resulting in a blurred translation between indoors and outdoors.

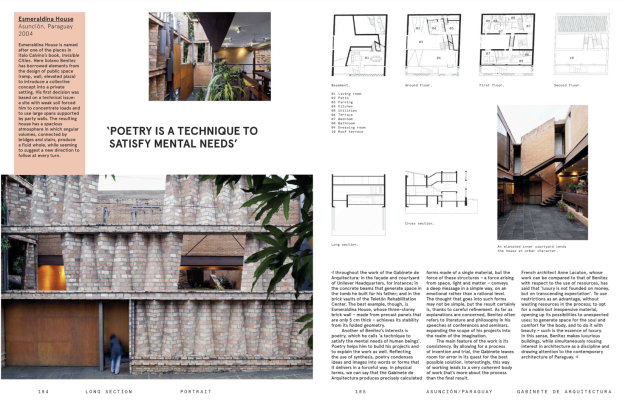

Esmeraldina House, Asunción, Paraguay 2004

Esmeraldina House is named after one of the places in Italo Calvino’s book, Invisible Cities. Here Solano Benitez has borrowed elements from the design of public space (ramp, wall, elevated plaza) to introduce a collective concept into a private setting. His first decision was based on a technical issue: a site with weak soil forced him to concentrate loads and to use large spans supported by party walls. The resulting house has a spacious atmosphere in which angular volumes, connected by bridges and stairs, produce a fluid whole, while seeming to suggest a new direction to follow at every turn. The striking ‘façade wall’ shields the house, forms a boundary and, at the same time, invites first-time visitors to discover an inner world.

Teletón Rehabilitation Center, Asunción, Paraguay 2012

The Teletón Foundation is an NGO dedicated to the rehabilitation of disabled children. The stages of construction for its accommodation in Asunción relied on funds from annual donations. Thus the project consists of various pavilions and interventions that were completed as money became available for their construction. Every material – new, used, recycled – that went into the project reflects the ethics and efforts of those who contribute to the foundation. Highlights of the Teletón Rehabilitation Center include brick vaulting at the entrance – components were made on site – and the swimming pavilion, with its roof of inverted pyramids. Such features enhance the evocative artificial landscape of the complex.

author: gustavo hiriart

originally published in Mark #42, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Pingback: Ensayo y error – Gabinete de Arquitectura | Gustavo Hiriart